to top

15 April 2024 (Monday)

4:30pm – 6pm EDT

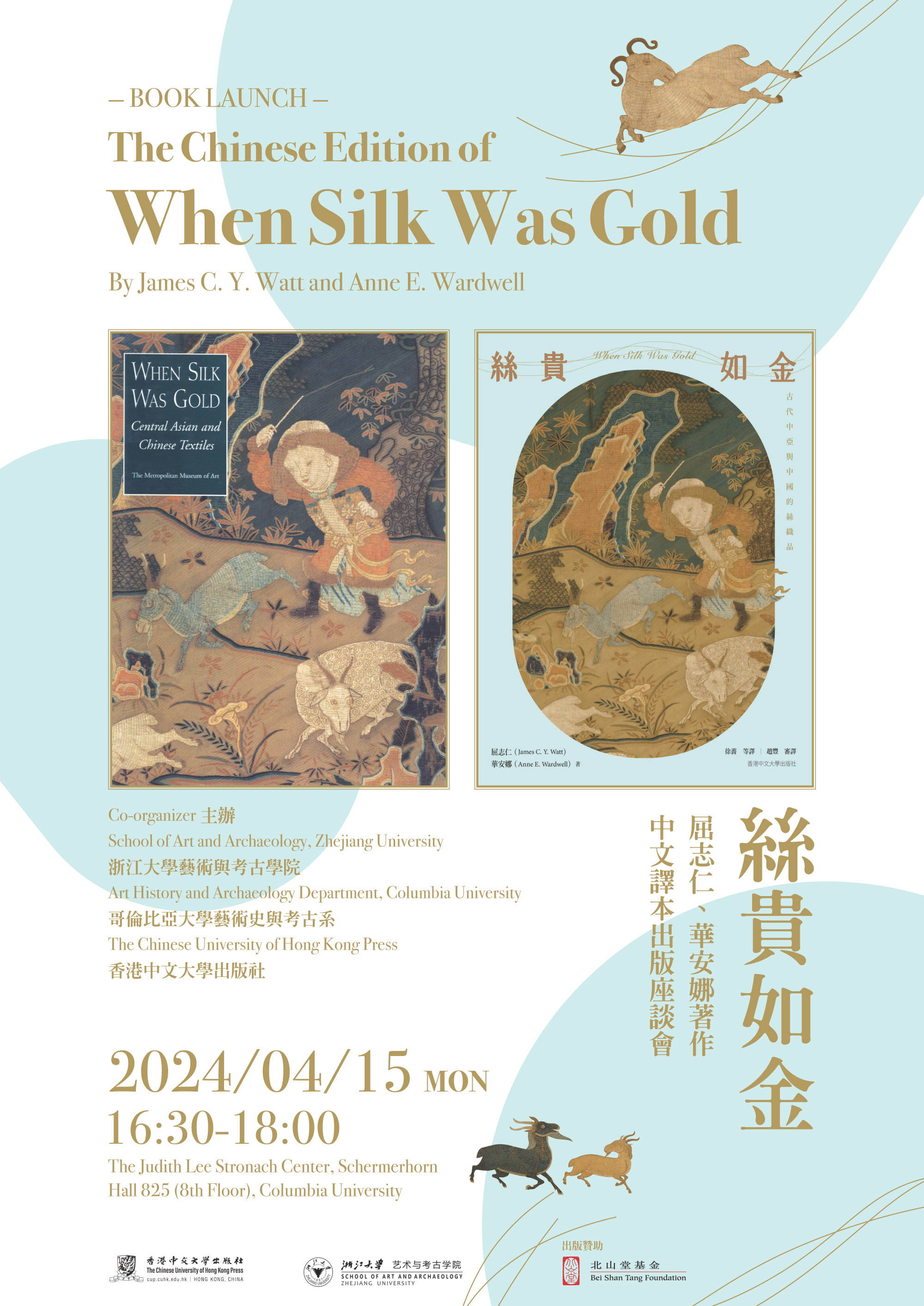

When Silk Was Gold is the catalogue for the first exhibition devoted exclusively to luxury silks and embroideries produced in Central Asia and China from the eighth to the early fifteenth century. Drawn from the collections of The Metropolitan Museum of Art and The Cleveland Museum of Art, the textiles are remarkable not only for their dazzling display of technical virtuosity but also for their historical significance, reflecting in their techniques and patterns shifts in the balance of power between Central Asia and China that occurred as dynasties rose and fell and empires expanded and dissolved.

The finest products of imperial embroidery and weaving workshops in the Middle Ages were among gifts presented by emperors and members of the imperial family to other rulers, emissaries, and distinguished persons. Richly woven textiles were also highly coveted as commercial goods. Transported across vast distances in unprecedented numbers to places as remote as the courts and church treasuries of Europe, they formed the mainstay of international commerce. Under the Yuan dynasty (1279–1368), textiles were an important part of the Mongol patronage of Buddhist sects in Tibet, which was an important means of solidifying Mongol-Tibetan relations.

The material presented in this volume significantly extends what has been known to date of Asian textiles produced from the Tang (618–907) through the early Ming period (late 14th–early 15th century), and new documentation gives full recognition to the importance of luxury textiles in the history of Asian art. Costly silks and embroideries were the primary vehicle for the migration of motifs and styles from one part of Asia to another, particularly during the Tang and Mongol (1207–1368) periods. In addition, they provide material evidence of both the cultural and religious ties that linked ethnic groups and the impetus to artistic creativity that was inspired by exposure to foreign goods.

The demise of the Silk Roads and the end of expansionist policies, together with the rapid increase in maritime trade, brought to an end the vital economic and cultural interchange that had characterized the years preceding the death of the Ming-dynasty Yongle emperor in 1424. Overland, intrepid merchants no longer transported silks throughout Eurasia and weavers no longer traveled to distant lands. But the products that survive from that wondrous time attest to a glorious era—when silk was resplendent as gold.